Asteroid Impact

An asteroid five miles wide would cause major extinctions. There is no question that a cosmic interloper will hit Earth, and we won’t have to wait millions of years for it to happen. In 1908 a 200-foot-wide comet fragment slammed into the atmosphere and exploded over the Tunguska region in Siberia, Russia, with nearly 1,000 times the energy of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Astronomers estimate similar-sized events occur every one to three centuries.

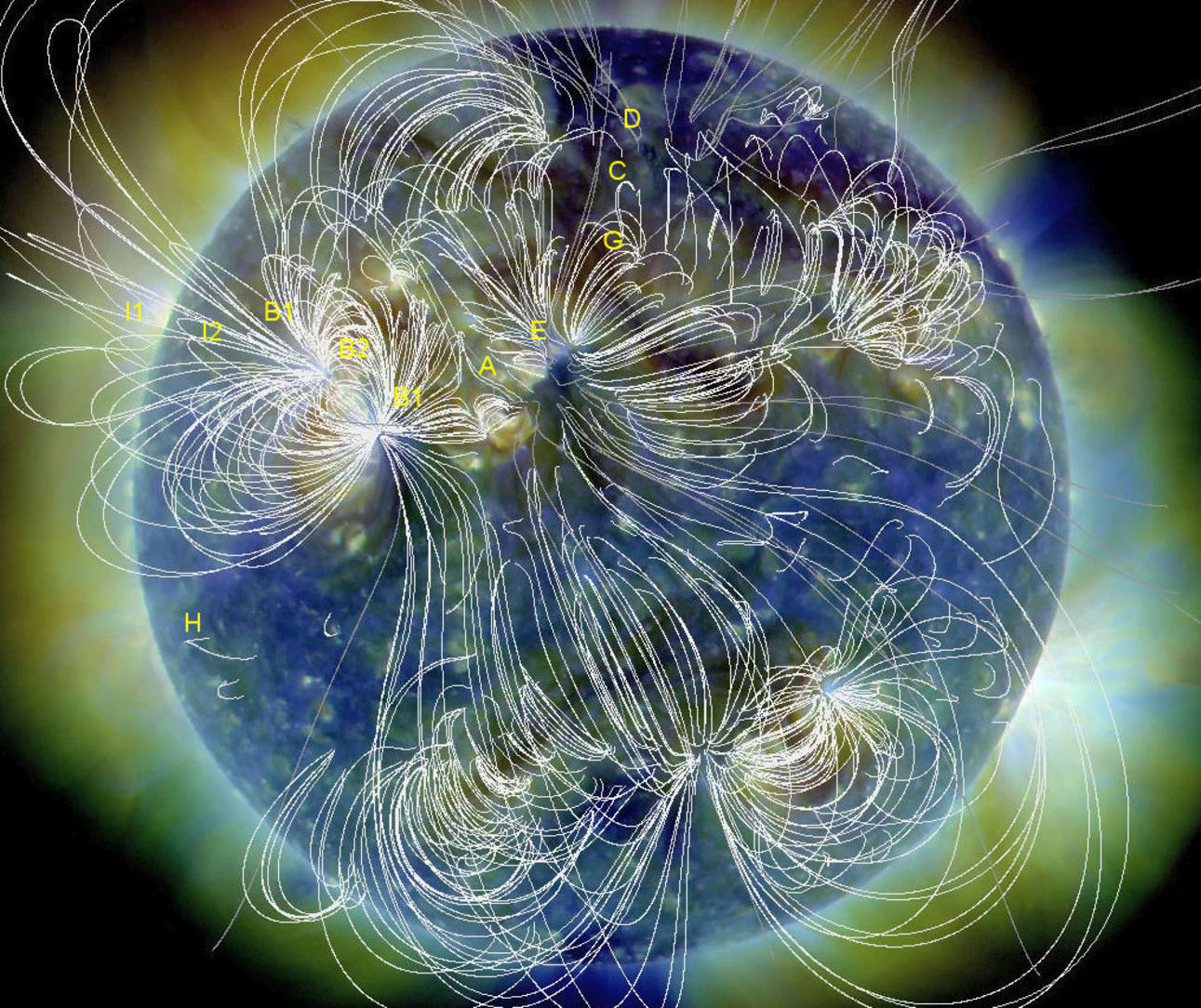

Giant solar flares

Enormous magnetic outbursts on the sun that bombard Earth with a torrent of high-speed subatomic particles. Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field negate the potentially lethal effects of ordinary flares. But while looking through old astronomical records, Bradley Schaefer of Yale University found evidence that some perfectly normal-looking, sunlike stars can brighten briefly by up to a factor of 20. Schaefer believes these stellar flickers are caused by superflares, millions of times more powerful than their common cousins. Within a few hours, a superflare on the sun could fry Earth and begin disintegrating the ozone layer. Although there is persuasive evidence that our sun doesn’t engage in such excess, scientists don’t know why superflares happen at all, or whether our sun could exhibit milder but still disruptive behavior. And while too much solar activity could be deadly, too little of it is problematic as well. Sallie Baliunas at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics says many solar-type stars pass through extended quiescent periods, during which they become nearly 1 percent dimmer. That might not sound like much, but a similar downturn in the sun could send us into another ice age. Baliunas cites evidence that decreased solar activity contributed to 17 of the 19 major cold episodes on Earth in the last 10,000 years.

Rogue black holes

Their gravity is so strong they swallow everything, even the light that might betray their presence. David Bennett of Notre Dame University in Indiana managed to spot two black holes recently by the way they distorted and amplified the light of ordinary, more distant stars. Based on such observations, and even more on theoretical arguments, researchers guesstimate there are about 10 million black holes in the Milky Way. These objects orbit just like other stars, meaning that it is not terribly likely that one is headed our way. But if a normal star were moving toward us, we’d know it. With a black hole there is little warning. A few decades before a close encounter, at most, astronomers would observe a strange perturbation in the orbits of the outer planets. As the effect grew larger, it would be possible to make increasingly precise estimates of the location and mass of the interloper. The black hole wouldn’t have to come all that close to Earth to bring ruin; just passing through the solar system would distort all of the planets’ orbits. Earth might get drawn into an elliptical path that would cause extreme climate swings, or it might be ejected from the solar system and go hurtling to a frigid fate in deep space.

Nanotechnology Disaster

Within a few decades, maybe sooner, it should be possible to build microscopic robots that can assemble and replicate themselves. They might perform surgery from inside a patient, build any desired product from simple raw materials, or explore other worlds. All well and good if the technology works as intended. Then again, consider what K. Eric Drexler of the Foresight Institute calls the “grey goo problem” in his book Engines of Creation, a cult favorite among the nanotech set. After an industrial accident, he writes, bacteria-sized machines, “could spread like blowing pollen, replicate swiftly, and reduce the biosphere to dust in a matter of days.” How do you get so many assemblers? First you build a few in the lab. Then you set the assemblers to build other assemblers. These new assemblers will begin building more machines in turn. The manufacturing rate becomes exponential, doubling with each generation.

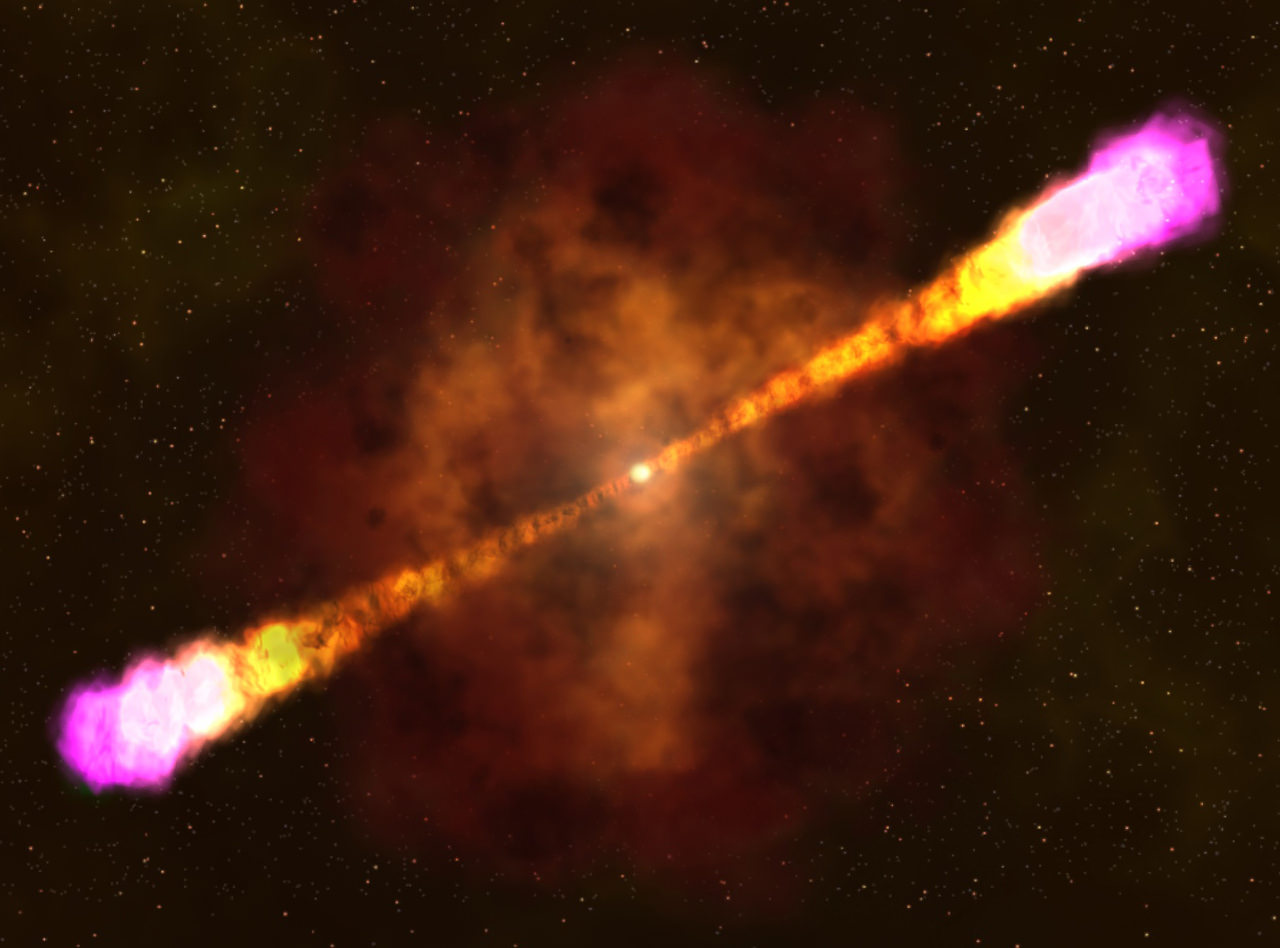

Gamma-ray burst

Extremely energetic explosions that have been observed in distant galaxies. They are the brightest electromagnetic events known to occur in the universe. Earth’s atmosphere would initially protect us from most of the burst’s deadly X rays and gamma rays, but at a cost. The potent radiation would cook the atmosphere, creating nitrogen oxides that would destroy the ozone layer. Without the ozone layer, ultraviolet rays from the sun would reach the surface at nearly full force, causing skin cancer and, more seriously, killing off the tiny photosynthetic plankton in the ocean that provide oxygen to the atmosphere and bolster the bottom of the food chain.

Biotech disaster

While we are extinguishing natural species, we’re also creating new ones through genetic engineering. Genetically modified crops can be hardier, tastier, and more nutritious. Engineered microbes might ease our health problems. And gene therapy offers an elusive promise of fixing fundamental defects in our DNA. Then there are the possible downsides. Although there is no evidence indicating genetically modified foods are unsafe, there are signs that the genes from modified plants can leak out and find their way into other species. Engineered crops might also foster insecticide resistance. Longtime skeptics like Jeremy Rifkin worry that the resulting superweeds and superpests could further destabilize the stressed global ecosystem. Altered microbes might prove to be unexpectedly difficult to control. Scariest of all is the possibility of the deliberate misuse of biotechnology. A terrorist group or rogue nation might decide that anthrax isn’t nasty enough and then try to put together, say, an airborne version of the Ebola virus. Now there’s a showstopper.

40 Great Prepping Tips That Anyone Can Put to Use

Alien Invasion

The history of human exploration and exploitation suggests the most likely danger is not direct conflict. Aliens might want resources from our solar system (Earth’s oceans, perhaps, full of hydrogen for refilling a fusion-powered spacecraft) and swat us aside if we get in the way, as we might dismiss mosquitoes or beetles stirred up by the logging of a rain forest. Aliens might unwittingly import pests with a taste for human flesh, much as Dutch colonists reaching Mauritius brought cats, rats, and pigs that quickly did away with the dodo. Or aliens might accidentally upset our planet or solar system while carrying out some grandiose interstellar construction project. The late physicist Gerard O’Neill speculated that contact with extraterrestrial visitors could also be socially disastrous. “Advanced western civilization has had a destructive effect on all primitive civilizations it has come in contact with, even in those cases where every attempt was made to protect and guard the primitive civilization,” he said in a 1979 interview. “I don’t see any reason why the same thing would not happen to us.”

Ecosystem collapse

To meet the demands of the growing population, we are clearing land for housing and agriculture, replacing diverse wild plants with just a few varieties of crops, transporting plants and animals, and introducing new chemicals into the environment. At least 30,000 species vanish every year from human activity, which means we are living in the midst of one of the greatest mass extinctions in Earth’s history. Stephen Kellert, a social ecologist at Yale University, sees a number of ways people might upset the delicate checks and balances in the global ecology. New patterns of disease might emerge, he says, or pollinating insects might become extinct, leading to widespread crop failure. Or as with the wolves of Isle Royale, the consequences might be something we’d never think of, until it’s too late.

Reversal of Earth’s magnetic field

A change in a planet’s magnetic field such that the positions of magnetic north and magnetic south are interchanged (not to be confused with geographic north and geographic south). The Earth’s field has alternated between periods of normal polarity, in which the predominant direction of the field was the same as the present direction, and reverse polarity, in which it was the opposite. There have been 183 reversals over the last 83 million years. The latest, the Brunhes–Matuyama reversal, occurred 780,000 years ago, and may have happened very quickly, within a human lifetime. In August 2018, researchers reported a reversal lasting only 200 years. When the poles do reverse, Earth’s magnetic field could get weaker—but its strength is already quite variable, so that’s not necessarily unusual, and there’s no indication it will vanish entirely, according to NASA. However, if the magnetic field gets substantially weaker and stays that way for an appreciable amount of time Earth will be less protected from the oodles of high-energy particles that are constantly flying around in space. This means that everything on the planet will be exposed to higher levels of radiation, which over time could produce an increase in diseases like cancer, as well as harm delicate spacecraft and power grids on Earth.

Global Warming

By the end of the century, the global temperature is likely to rise more than 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit. This rise in temperature is the ominous conclusion reached by two different studies using entirely different methods published in the journal Nature Climate Change. One study used statistical analysis to show that there is a 95% chance that Earth will warm more than 2 degrees at century’s end, and a 1% chance that it’s below 1.5 C. The second study analyzed past emissions of greenhouse gases and the burning of fossil fuels to show that even if humans suddenly stopped burning fossil fuels now, Earth will continue to heat up about two more degrees by 2100. It also concluded that if emissions continue for 15 more years, which is more likely than a sudden stop, Earth’s global temperature could rise as much as 3 degrees. Why two degrees? The 2 degree mark – that’s a rise of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit in global temperature – was set by the 2016 Paris Agreement. It was first proposed as a threshold by Yale economist William Nordhaus in 1977. The climate has been warming since the burning of fossil fuels began in the late 1800s during the Industrial Revolution, researchers say. If we surpass that mark, it has been estimated by scientists that life on our planet will change as we know it. Rising seas, mass extinctions, super droughts, increased wildfires, intense hurricanes, decreased crops and fresh water and the melting of the Arctic are expected. The impact on human health would be profound. Rising temperatures and shifts in weather would lead to reduced air quality, food and water contamination, more infections carried by mosquitoes and ticks and stress on mental health, according to a recent report from the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health. Currently, the World Health Organization estimates that 12.6 million people die globally due to pollution, extreme weather and climate-related disease. Climate change between 2030 and 2050 is expected to cause 250,000 additional global deaths, according to the WHO.

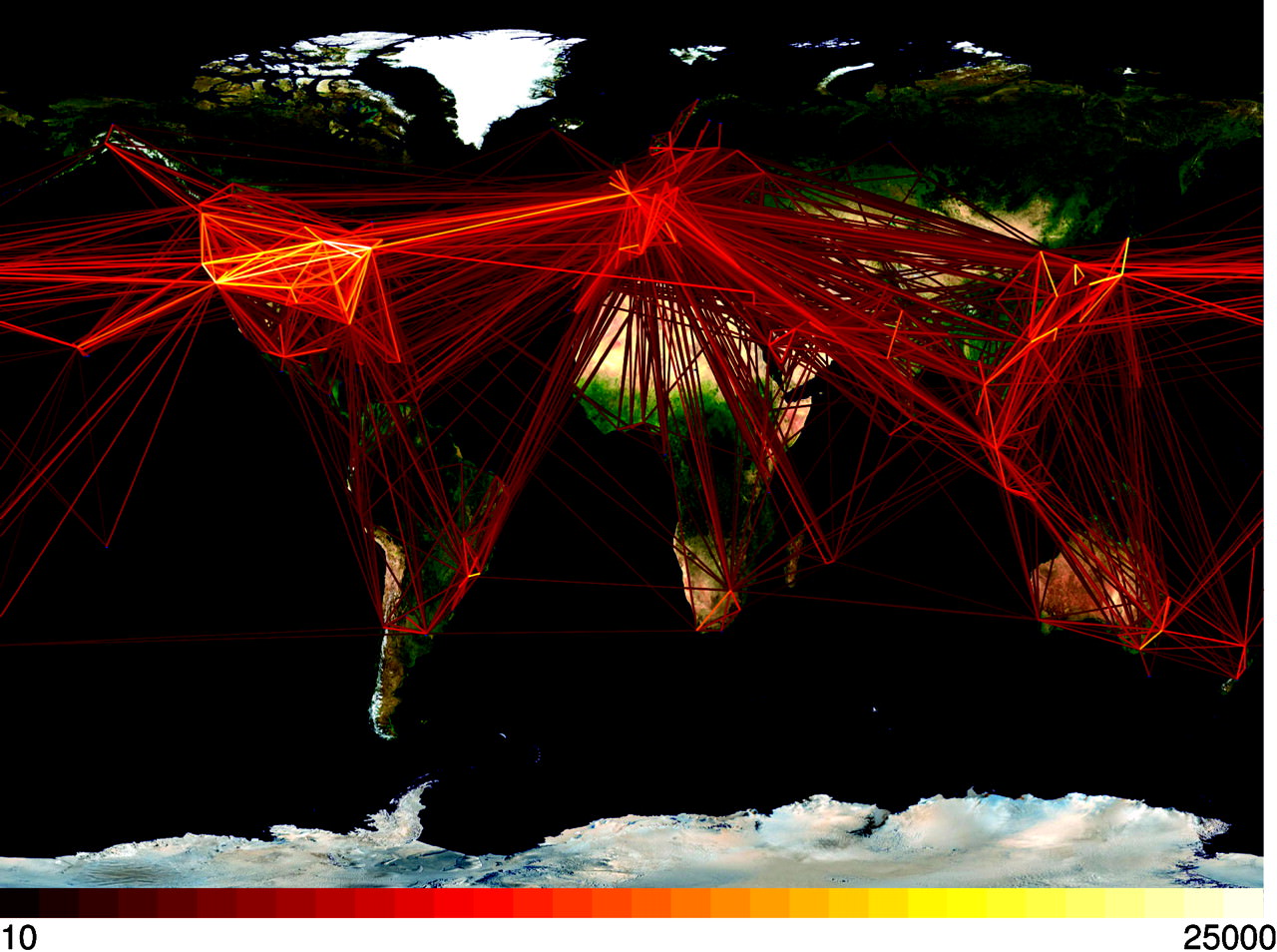

Global epidemics

Germs and people have always coexisted, but occasionally the balance gets out of whack. The Black Plague killed one European in four during the 14th century; influenza took at least 20 million lives between 1918 and 1919; the AIDS epidemic has produced a similar death toll and is still going strong. From 1980 to 1992, reports the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, mortality from infectious disease in the United States rose 58 percent. Old diseases such as cholera and measles have developed new resistance to antibiotics. Intensive agriculture and land development is bringing humans closer to animal pathogens. International travel means diseases can spread faster than ever. Michael Osterholm, an infectious disease expert who recently left the Minnesota Department of Health, described the situation as “like trying to swim against the current of a raging river.” The grimmest possibility would be the emergence of a strain that spreads so fast we are caught off guard or that resists all chemical means of control, perhaps as a result of our stirring of the ecological pot. About 12,000 years ago, a sudden wave of mammal extinctions swept through the Americas. Ross MacPhee of the American Museum of Natural History argues the culprit was extremely virulent disease, which humans helped transport as they migrated into the New World.

Flood-basalt volcanism

The great continental flood-basalt eruptions of the geological past are the largest eruptions of lava on Earth, with known volumes of individual lava flows exceeding 2000 cubic kilometres. If there is a causal link between flood basalt events and mass extinctions, it may lie in the environmental impact of the gases released, because basalt eruptions are not particularly explosive. Several kinds of environmental effects have been suggested, including climatic cooling from sulphuric acid aerosols, greenhouse warming from CO2 and SO2 gases, and acid rain. Basaltic magmas are often very rich in dissolved sulphur, and sulphuric acid aerosols formed from sulphur volatiles (largely SO2) are injected into the stratosphere by convective plumes rising above volcanic vents and fissures. Indirect environmental effects include changes in ocean chemistry, circulation, and oxygenation, especially from basaltic volcanism associated with large submarine oceanic plateaus that may represent flood basalt eruptions in an oceanic environment.

By WannaWanga

<<Best selection of SURVIVAL BOOKS>>

Self-sufficiency and Preparedness solutions recommended for you:

BulletProof Home (A Prepper’s Guide in Safeguarding a Home)

Food for Freedom (If I want my family to survive, I need my own food reserve)

Alive After the Fall (Build yourself the only unlimited water source you’ll ever need)